Resource Page

This page is all about water quality. Wondering what some terms on this website mean, or how watersheds work? Scroll down for more information!

Curious how you can do your part to protect stormwater? Check out the How Can You Help page. It has ideas for things you can do at your home and in your neighborhood to be a good steward of the environment.

Please get involved and come back often. You are an important part of stormwater management. Happy reading!

Ver esta pagina en Español?

Quick Links

The Big Picture

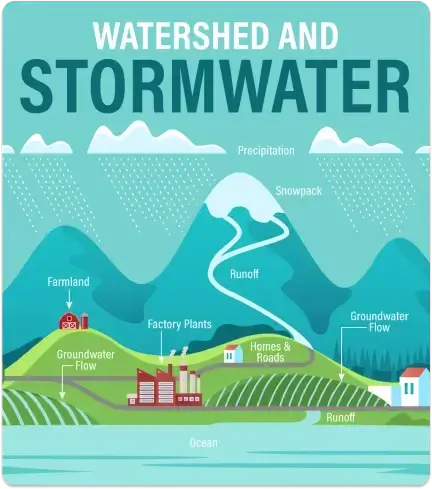

What is a Watershed?

Have you ever built a sandcastle at the beach and poured water on it? It probably looked like the water made a river as it cut through the sand and found its way back to the ocean. Water has an amazing way of always finding the lowest point, which is how watersheds are formed. When it rains, the rainwater flows downhill, gathering to forge rivers and creeks. It pools in low points to create ponds, lakes, and oceans. The watershed is the whole area that drains to the pond, lake, or ocean. Rainwater is called stormwater when it flows over the land.

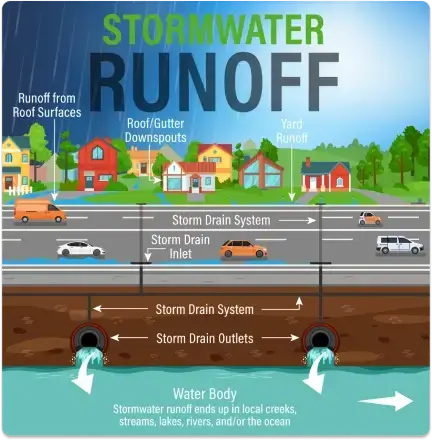

Stormwater can also be called runoff because rain can run off of sidewalks, roofs, parking lots, and other surfaces into creeks, channels, and stormdrains. Runoff can even happen when it is not raining! Daily activities like watering your lawn, hosing down sidewalks, and car washing all add to runoff, specifically called dry weather runoff because it occurs in dry weather.

Keep in mind that a watershed is not decided by political boundaries. Instead, it is shaped by hills and valleys. That is why we have watersheds that serve multiple cities and counties, and cities and counties that are in multiple watersheds. Things get tricky as each city establishes its own water management policies and spending priorities. Keep reading to learn about watershed planning and how we can work together to protect our watersheds!

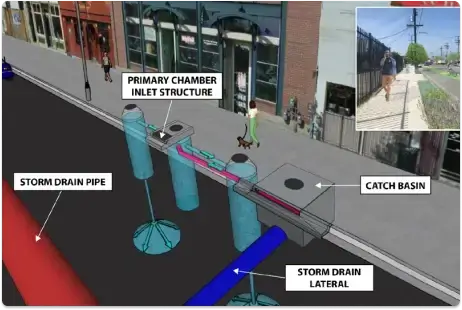

Where Does Stormwater Go?

Stormwater disappears into a storm drain system, called a stormwater MS4, which stands for Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (or MS4 for short!). The MS4 includes publicly owned storm drains, gutters, roadside ditches, grassy swales, sediment ponds, and similar features that hold and move stormwater. They are called “separate” because they carry only stormwater and are distinct from the sanitary sewers that carry raw sewage (whatever goes down the drain when we shower or flush the toilet). Unlike sewage, which is cleaned up at a water reclamation plant, the MS4 drains directly to rivers, creeks, lakes, and the ocean unless the stormwater is captured before it gets to the MS4. Water reclamation plants treat sewage and use the treated water for irrigation. So, your city or county is responsible for removing the pollution the stormwater picks up from its land (and for some cities, that is a LOT of land!).

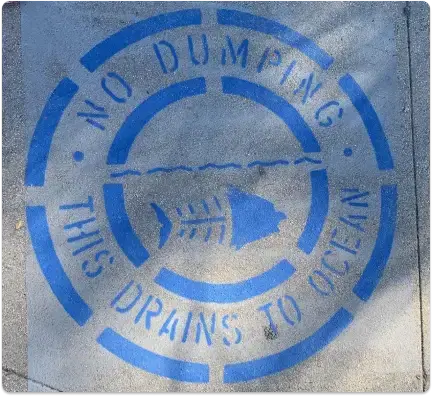

Eventually, the MS4 flows to a receiving water, which is a fancy term for an ocean, stream, river, pond, lake or other body of water into which stormwater flows. The receiving water receives all the water from its watershed. The signs that say “No Dumping - This drains to ocean” are serious – nothing cleans up the water from that spot before it reaches the ocean!

Why and How Do We Make Rules to Protect Stormwater?

When it rains, the sky gives the earth a shower. All the pollution gathered on the land from cars, industries, pets, and people is washed down by the flowing water until it reaches the receiving water. We call this pollutant loading. This pollution can be bad for human health and the environment. Some pollutants can make people sick if we swim in the water or somehow swallow the water. Other pollutants can harm the fish and other animals living in the water.

Sometimes, these pollutants build up over time. This happens when pollutants stay in one place because there is no water or rainwater to wash them away. More and more pollutants pile up during the dry days or months, literally building up over time.

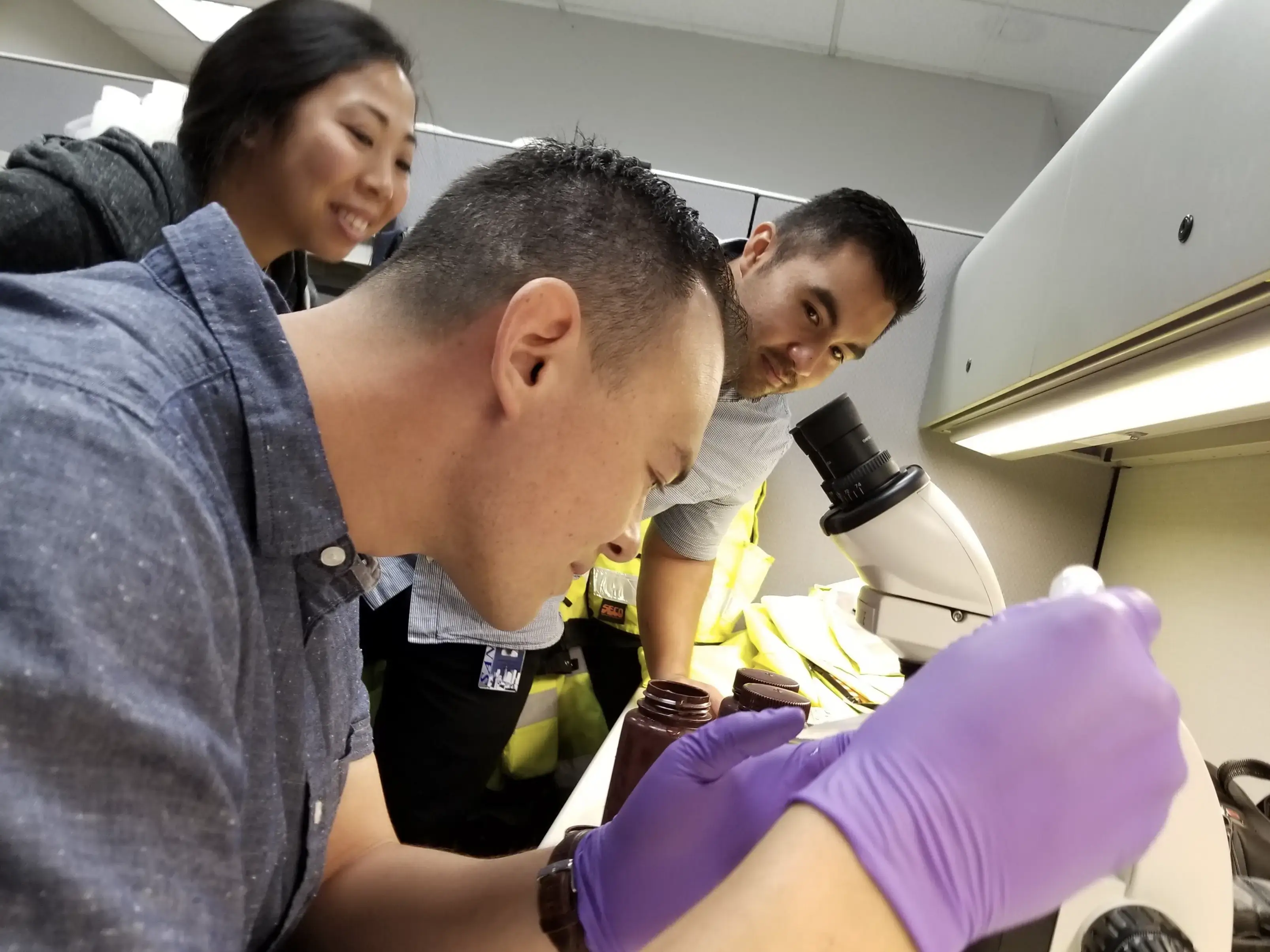

How do we know the water quality of stormwater?

What is water quality?

Water quality means how much (or hopefully how little!) pollution is in water. Some pollutants, like viruses and certain bacteria, are unsafe for humans because they can make us sick. Other pollutants, like metals, can harm an ecosystem because they are bad for fish and other things that live in the water. “Good” water quality means all the pollutants are below the levels science says are safe for humans and our ecosystems.

Regulators like EPA and the Regional Board set limits for how much of a pollutant is allowed in a certain waterbody. These regulations are specific for each waterbody and each pollutant. For example, Lake A may have limits to how much a certain bacteria can enter it, and how much zinc can enter it. But, the amount of zinc allowed is measured differently than the amount of bacteria. Another lake, Lake B, may also have limits on bacteria, but those limits may be different than Lake A. To make sense of all these numbers, we use waterbody pollutant combinations. Each waterbody has its own waterbody pollutant combination. Check out the Water Quality Dashboard page for more information on our local waterbodies.

Read on for more information about specific types of pollutants:

Pathogens

A pathogen is a virus, parasite, or certain form of bacteria that can make humans sick, especially if the water is swallowed or in contact with skin for too long. The pathogens that make us sick are really hard to identify when we collect samples and send them to a laboratory for testing. Instead, we look for “fecal indicator bacteria,” such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) and enterococcus because they indicate there is fecal matter (poop) in the water suggesting that pathogens that make us sick may also be in the stormwater. Fecal indicator bacteria may come from human, pet, livestock, and wildlife waste. It is more common in heavily populated areas or farmed areas. Untreated human waste (poop) is the most concerning because it is most likely to have pathogens that make us sick.

Metals

Different types of metals, such as Lead, Copper, Zinc, Mercury, Arsenic, and Selenium, can find their way into stormwater. They can make plants and animals in the water sick, and even humans. Metals can come from all sorts of places, including car tires, rusty and leaky cars, car brakes, roofs, gutters, rusty fences, dumping paint or used motor oil in the trash or storm drain, and roof and boat cleaning chemicals.

Nutrients

Legacy Pollutants and Forever Chemicals

Is history repeating itself? A present-day example is a group of chemicals called PFAS, which stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS are used in common household products like non-stick cookware, clothing, fire-fighting, manufacturing, and fast food packaging. Although some US companies stopped using the more harmful PFAS chemicals, they continue to enter the watershed from imported goods. PFAS are referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in nature and continue to build up in water, air, fish, and soil. Scientists and researchers are working hard to understand and find ways protect people from PFAS in drinking water.

Friederici, Peter, and May-June 2012. “Is DDT Here to Stay?” Audubon, 13 Apr. 2016, https://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june-2012/is-ddt-here-stay.

Current Use Pesticides

Pesticides are chemicals used to kill pests, like ants, mosquitoes, beetles, aphids, termites, ticks, rats and mice. Sometimes we use pesticides to protect food crops and sometimes to protect building and our bodies. Humans have used pesticides for as long as we have been growing food; before using manmade chemicals people used ashes, crushed plants that are poisonous to insects, and even urine! Some pesticides, like DDT are banned but the pests that they control are still around so new pesticides are used instead. Runoff carries pesticides that are in the soil to the receiving water. Unfortunately, many of these pesticides can still be toxic to plants and animals in receiving water.

How do you check water quality?

Using Stormwater as a “Beneficial Resource”

When thinking about stormwater as a resource, we think about capturing and reusing it. We can use it to do things like water our lawns, or let it soak into the ground to fill up our aquifers. Aquifers are places underground where water is naturally stored. We often get drinking water from aquifers.

The capture volume is the amount of stormwater a project could hold at any given time. More and bigger projects mean that we can clean up more stormwater! It all adds up to make a huge difference!

Capture volume is commonly measured in acre-feet. One acre-foot equals about 326,000 gallons, or enough water to cover an acre of land, about the size of a football field, one foot deep. It would only take about 500 acre-feet to fill Dodger Stadium! An average California household uses between one-half and one acre-foot of water per year for indoor and outdoor use combined.

We capture stormwater through best management practices, which we call BMPs. We have many BMPs to choose from when deciding how to best capture stormwater. Some are better in some places, and some are better in others. For example, BMPs may be different for capturing stormwater in a park versus capturing it in a parking lot.

Some of the many BMPs we can use are listed below:

Rain Garden

Dry Well

Low Flow Diversion BMP

Detention, retention, and infiltration basins

Detention, retention, and infiltration basins are other BMPs to capture stormwater before it goes to the storm drain. Each of these basin BMPs operates a little differently, but all provide flooding and water quality benefits. Infiltration basins capture stormwater and hold it until it has all soaked into the ground. Detention basins hold stormwater until the flooding risk passes and release treated water back to MS4 and receiving waters.

Some BMPs, like rain gardens, are called green infrastructure because we use nature in place of gutters, pipes, and tunnels. Basically, green infrastructure cleans and soaks up stormwater where it falls. Most of the time green infrastructure helps protect communities from flooding or extreme heat, or makes air, soil and water quality better. Green infrastructure comes in all sizes: small like a rain barrel at your house, medium like a rain garden on a city street, or large like a wetland.

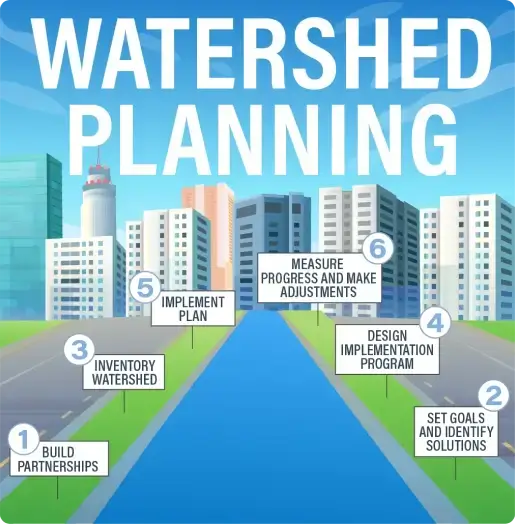

Watershed Planning

What is watershed planning?

Nature-based solutions are inspired by nature and copy natural processes to manage water. A nature-based solution might restore an existing natural system, or it might use a natural process where one previously did not exist, all while helping humans' well-being and increasing the number and variety of animals and plants in the area. A natural system is anything that copies what you might find in nature, like wetlands, streams, creeks, and grassy areas. Our urban environments and people living in them benefit by having more open spaces, wildlife, and beautiful plants.

Non-structural solutions focus on keeping open space, protecting natural systems, cleaning streets and MS4s, educating community members about how to help, and reducing paved areas that cannot soak up water. Many times, these solutions try to keep stormwater near where it landed on the ground. It is hard to measure how much non-structural solutions reduce pollution because changes to human behaviors happen everywhere. If we all work together to protect our watersheds through non-structural solutions, it can add up to make a big difference.

How will Measure W help?

Some of the money is for individual cities to help pay for their stormwater programs. Some of the money is for regional projects that meet the Measure W's goals. The program lets agencies and community organizations apply for money to pay for their projects. The Safe, Clean Water Program committees select the best projects that will help clean the region's waters. To apply for Measure W funding, stormwater projects need to capture it, clean it, make it safe, and make it for everyone.

What are the “benefits” of watershed planning?

The end goal of Watershed planning is to meet MS4 permit requirements, and working to achieve that goal also gives many benefits to the wider community, including the following:

Reduce the Heat Island Effect

Reduce Flooding

Clean Streets

A project that helps clean up pollution on streets has “clean streets” benefits. Creating clean streets is important because it keeps grime, debris, and pollutants from entering stormwater. It also helps keep storm drains open so that runoff does not back up to the roads. And it makes our roads look better too!

Increase Parks and Green Space

Parks and green spaces in our cities have benefits ranging from decreasing air and water pollution, noise levels, and the heat island effect, to offering places for people to walk, run, and play. Green spaces help make us happier and healthier people by providing places to meet or exercise outdoors. Increasing parks and green space also means we are turning paved surfaces that do not soak up stormwater into grassy or vegetated land that can soak up stormwater. Wildlife benefits too! Parks and green space create habitat for birds and other urban wildlife.

Augment Water Supply

Create Jobs

Some of the projects that we are planning to build in our watershed need people to study the land, design/engineer/permit the project, construct the project, and operate/maintain it. All these activities will create jobs!

Beautify Neighborhoods

Benefit Disadvantaged Communities

Projects benefitting disadvantaged communities are projects that have a positive effect on communities with lower income levels. Disadvantaged communities often experience poverty, unemployment, and air and water pollution. According to the California Public Utilities Commission, they also often have hazardous wastes in the area, and asthma and heart disease are common. These communities have historically received less community support, have fewer parks and less green space. Since the stormwater projects we work on are designed to provide community benefits you just read about they can have a strong positive effect on disadvantaged communities when built in those areas.